"You Can't Get Then From Now" Part 1 - by Dr. William Moritz

Published in Journal: Southern California Art Magazine (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art), No. 29, Summer 1981

Words sustain little power to evoke the intricate surface textures of the life in bygone days. The meaning of a phrase like "a well-dressed man" changes from hour to hour, street to street, brain to brain. Even so epic a verbalization as Proust's novel In Search of Lost Times conveys best the universal, abstract emotions - the Platonic forms - leaving the reader to sigh, "Oh yes, I know just how he feels!" while as often as not that same reader remains ignorant of the cut of nightgown worn by the boy or whether a doily habitually graced his bedside table. Or indeed, this reader may blissfully conjecture some "contemporary" style pajama or flushed nudity that might have horrified poor Proust. The recovery of details about gesture and fashion we must leave to the carte-de-visite, etchings in magazines, stereopticon views, and a precious few images flickering through surviving cinematograph reels.Unlike the Paris of Proust, the Los Angeles of the World War II era seems completely, authentically documented on film. Speaking of pictures, Life magazine shows us more than we could want to know about shoulder pads and nylon seams, jitterbugs and conga lines, valiant nurses and sinister spies, while through the magic of Hollywood feature films these things spring to life and speak to us with the lips of Margaret Sullavan and Carmen Miranda, Humphrey Bogart and Ronald Reagan - and the American public. Whatever may be lacking from the sometimes naive idealism of the Hollywood feature can be supplied from newsreels and documentaries of the battlefields and defense plants. And a few seconds' glance at the steaming streets of Dresden or the bulldozers at Auschwitz or the human shadow etched on a wall at Hiroshima haunt the corners of our minds with a million unspoken sorrows and a lurking, unspeakable terror that this must have been a grotesque and horrible age, somehow different from today - more vicious, less sophisticated, or...?

But among the miles and miles of film documents from the 1940-1945 period, half-a-dozen little movies seem truly extraordinary: they are documents of the human spirit instead of records of the primate society. For these nonobjective films by Oskar Fischinger and the Whitney brothers, in stunning gestures of absolute creation, miraculously breathe a serene confidence in the face of a world gone mad, as if, somehow (perhaps like Malevich with the Russian revolution) the societal breakdown had freed these men to pursue their personal spiritual development beyond conventional expectations.

Can we know how they managed? The films themselves, with their pure, minimal geometries, stubbornly refuse to admit any detail of the everyday turmoil that surrounded their making. So I have wandered around the Los Angeles film scene like a modern Vasari gathering gossip about the lives of these artists, in the hope that these verbal snapshots I have reconstructed may afford us a new perspective on a revolutionary threshold in art.

Fischinger with two Plexiglass paitings from Motion Painting No. 1

I. Oskar Fischinger

In 1940 Oskar Fischinger was forty years old. [1] Since 1923 in Germany, he had supported himself as an independent filmmaker, creating at least thirty-five abstract experimental films which had met with success in Europe. He supplemented his income from film sales and rentals with commercial work including advertising films, titles and special effects. His Composition in Blue (1935) had won grand prizes at festivals in Venice and Brussels*, so Paramount brought him to Hollywood in 1936; just in time, since the Nazi government was busy declaring abstract art degenerate.

But Fischinger did not fare well in the Hollywood studio system. At first he spoke no English, and despite bilingual secretaries, he could not express his ideas easily or well. He much preferred his independent production methods, since he found that the studios' factory "division of labor" most often meant neutralizing artistic goals, as each person involved required a compromise. Oskar's contract with Paramount ended after six months when he insisted on working with nonobjective imagery in color, while the studio demanded a black-and-white piece with representational effects. An Optical Poem, produced privately for MGM in 1937, enjoyed critical success but did not bring in enough box-office profits (largely because boycott against the axis powers and the beginning of World War II cut off the lucrative European and Asian markets) to encourage MGM's commissioning another abstract short. And Oskar's year at Disney (1939) working on Fantasia ended in a depressing repeat of the Paramount stand-off. [2]

Unfortunately, Hollywood studios seemed like the major avenue for producing color film in 35mm in America at that time; because the high cost of processing and printing required substantial funding, which Oskar could not hope to supply on his own; since the studios made their special effects and titles internally with regular staff members; and the United States did not have a well-defined "underground" film distribution system like France's cine-clubs, England's Film Society, etc., through which Oskar could expect a regular income from his own films.

Thus Fischinger's move to America proved physically as well as emotionally traumatic. Several people, including Oskar's agent Paul Kohner, warned them that, in Hollywood, one must always appear prosperous in order to seem successful, which is equated with "worth hiring." So while still employed at Paramount for a sumptuous $250 per week, the Fischingers (Oskar, Elfriede and their son Karl) moved into a fashionable apartment complex on the Sunset Strip: Normandy Village, built in imitation Tudor wood-beam cottages (two-story, $100 per month, furnished, maid service) with a stream meandering among them. Without the Paramount salary, the Fischingers faced financial difficulties. When Oskar left Berlin, the Nazi government officially forbade him to export any money or the negatives or prints of his films. Therefore Oskar only had with him in Hollywood single release prints of twelve sound films which had been brought to America by Universal, Paramount, and Paul Kohner for MGM earlier in the thirties. Before Oskar could offer any of these films for distribution, he had to strike duplicate negatives for additional prints; a prohibitively costly matter which was not fully accomplished until 1946. Optical Poem was financed in such a way that Oskar received $50 per week salary in addition to potential over all profits, but bookkeeping, managers, and legal fees ate up all the profits. Nevertheless, despite their restricted finances, the Fischingers maintained their chic Sunset Boulevard residence (discreetly moving to a cheaper bungalow without service in the same complex) for appearance's sake.

While waiting for adequate backing for a film project, Oskar channeled more and more of his energy into easel painting. In April, 1938, Oskar drove to New York, where he had two one-man shows of his paintings, and tried to arrange funding for an abstract film based on Dvorak's New World Symphony, to be shown at the New York World's Fair in 1939. Even though this Dvorak project found no subsidy, the trip to New York was a great turning point in Oskar's life, for he met there the Baronessa Hilla Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, who would dominate his fate for the next decade.

The Baroness von Rebay was one of the great eccentrics. Ten years older than Oskar, she had exhibited her paintings in avant garde salons in France and Germany since 1913, and through her adoration for Rudolf Bauer, she embraced nonobjective art during the twenties. In 1927 she met the American millionaire Solomon Guggenheim (then sixty-six) who fell in love with her and placed in her trust his sizeable resources to create an outstanding collection of artworks. Over the years she did assemble a veritable treasure-house of abstract paintings, and she established the Museum of Non-Objective Art (now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) in New York. She tirelessly proselytized for nonobjective art by circulating exhibitions and publishing catalogues, and through the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation she helped many abstract artists and filmmakers with scholarships, loans and jobs, aside from the purchase of artworks.

For Oskar, the Baroness seemed like a dream come true. This bountiful, German-speaking woman, enchanted by his films, autographed a copy of her latest catalogue: "To the Great Fischinger, in Friendship, June 18, 1938," and she immediately extended an invitation for him to stay at her estate in Connecticut while she was away in Paris. Two of Oskar's friends, art dealers Karl Nierendorf and Galka Scheyer, advised him that Miss Rebay could be of great help to him, but also warned him that she could be capricious and dangerous. In October 1938, Oskar was recalled to Hollywood and the Disney studios before he had a chance to find out how.

As soon as it became clear that Fantasia would not be the feature-length abstract film Oskar had wanted to make, he began corresponding with Hilla Rebay, hinting that she might arrange financing for a 100 minute nonobjective animation with music by Paul Hindemith, a friend of Oskar's from Berlin days who was then in America. The Baroness denied that she could supply the amount of money necessary for an animation feature, about $150,000, but she encouraged him to plan a short film that would be a certain crowd-pleaser for American audiences, so that it could be distributed as a short in movie-houses nationwide, resulting in great profits as well as a prestige "track-record" necessary to attract industry funding. Under the assumption that everyone loves a march, Oskar resolved to make a film based on Sousa's Stars and Stripes Forever.

Oskar's agent Paul Kohner arranged for $1,000 backing for this project from Henry Koster (of Koster-Pasternak Productions), and Oskar asked Rebay for an additional $2,000 necessary for the three minute film. In January 1940, she agreed, and on February 27, 1940, Oskar signed a contract with "Baronessa H. von Rebay" stating that in exchange for $2,000, he would give her one print of Study #8, one print of Composition in Blue, and two prints of An American March when finished, which amounted to more than $1,000 in laboratory costs. Furthermore, he promised to repay the $2,000, and as a guarantee, to "give possession" to the Baronessa a copy of each of his other films (with no indication that she had to return these copies, worth well over $2,000. Indeed she kept them, and argued for years with Oskar that they were hers).

One might suppose that Oskar did not understand exactly how unfavorable this English-language contract was to him, but surely his bilingual friends, lawyer Milton Wichner (who kindly accepted Oskar's paintings for fees), and Galka Scheyer must have told him. The truth of the matter is that Oskar was desperate. There were now three more Fischinger children, and the $75 per month rent. The family had only survived 1938 with help from friends and the European Film Fund for refugees. Oskar's take-home salary at Disney had been only $68 per week, and by the time American March contract was signed, Oskar had been out of work for nearly four months.

The brittle side of Hilla Rebay's personality became more evident the more Oskar dealt with her. She was hot-tempered and impetuous, and probably over-extended herself so that she had trouble keeping track of all of her various business affairs, and consequently was suspicious. She must have been aware that her tenuous position was dependent on Solomon Guggenheim's good will, so she was jealous of other people and institutions that might challenge her supremacy in the field of nonobjective art. The Museum of Modern Art in New York asked for Oskar's films late in 1939, but on January 11, 1940, on the eve of promising Oskar $2,000 for American March, Rebay wrote him that if he let the Museum of Modern Art have his films "of course I will not help you." In the same letter appears an unexpectedly cruel, domineering tone: "As Mr. Bauer is here his advice might be important to you...Most of your films in the past were only partly good and I don't know how much you have improved, but just the same the advice of a master of non-objectivity would be of tremendous importance to you."

Hilla's relationship with Rudolf Bauer was certainly a major factor in her increasing emotional distress during the forties. This is not the place for a full discussion of their rather byzantine association, but certain details are necessary for understanding Oskar's involvement during this period. Bauer was about the same age as Rebay, and she had idolized him since they both showed paintings in the Sturm exhibitions during World War I. She adopted many of his ideas into her paintings and theoretical writings, and championed him as "the greatest of all painters...whose every work of Non-objectivity is an accomplished masterpiece..." [3]

Not everyone agreed with the Baroness, so for example Karl Nierendorf wrote Oskar on February 26, 1940 (the day before Oskar signed the American March contract): "I have nothing to do with the Baroness, and I think it will be impossible for me to ever be on good terms with her, because her ideas about art are quite contrary to mine. She is still fighting against Kandinsky, and considers Bauer to be the top of modern art."

Rebay managed to buy almost all of Bauer's paintings for the Museum of Non-Objective Art, and she slanted her exhibits and publications to feature his work. Unfortunately, this meant that one could only see Bauer paintings in New York, or as part of a loan from the Museum of Non-Objective Art. Later, when Bauer had fallen out of favor with the Baroness, it meant that Bauer paintings could easily disappear from sight. This has led to an unjust neglect of Bauer's painting, which, while definitely derivative of Kandinsky, still contains many graceful, moving expressions. Precisely because of Rebay's promotion of Bauer's work during the thirties and forties, it was very much seen and quite influential, so no responsible history of abstract art can fail to discuss his work.

Oskar had known Bauer since the Berlin days when he visited Bauer's home, which was set up as a museum named Das Geistreich, "The Realm of the Spirit." While Oskar found Bauer pompous, and definitely preferred the paintings of Klee, Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Feininger, something of Bauer's serial compositions of the late twenties through the mid-thirties (the triptychs and tetra-ptychons with musical titles that Rebay used as illustrations in most of her publications), a sense of lightness and geometrical substitution, may have influenced Oskar's serial designs in films like Allegretto and Radio Dynamics, or in Oskar's serial paintings.

Despite Hilla von Rebay's derision, Oskar set about work on American March quite seriously, and wrote the Baroness regular informative letters:

...I am now starting to shoot the film. I have already done the first tests. It's going to be a very good work that presents something quite new in the field of optical rhythm. I have gained a whole series of new perceptions during this current work, and these perceptions will be expressed in this film: used and made effective. For example, color mixture, color mutation in rhythmic exchange of color fluctuations on the motion-picture screen, such as is only possible because of the quick image-exchange rate of 24 frames per second. Through this film will be opened, among other things, a wholly new view of the field of color science. The Static, the passive observations of former color science, will be superseded by the Dynamic. This step corresponds to penetrating from the surface into the depths. The clever part lies in fast color change, in the vibration of colors which results in rhythmic life that is accessible through dynamic, climactic gradation. The psychological effect throughout is pleasurable. Concerning the interesting particulars of the temporal intermittence of color mix (one after the other) in contrast to the spatial juxtaposition of color mix (side by side at the same time), one could now write a very interesting piece. However, the film must be finished first! (August 18, 1940, translated from German)

Radio Dynamics

Radio Dynamics

We know from laboratory receipts that by September 1940, Oskar made test shots of the transparencies that later appear in the stunning flicker and loop sequences of the film Radio Dynamics. Some of the color blending he discusses in this letter, then, probably refers to that material as well as the rich, smooth color modulations typical of An American March.

Despite the obvious care and serious thought Oskar expended on the production, when An American March was finally completed in time for Solomon Guggenheim's eightieth birthday party, February 1, 1941, Rebay felt obliged to send Oskar pages of sketches and notes criticizing the film's structure and color balance, claiming that if he used the flag at all, he should have introduced the star and stripe separately in a fugal development that came to a rousing climax with the final appearance of the complete flag. In the same letter she asks, with astonishing ignorance, about the academy leader:"...Was that long empty stretch with numbers flying by just a fragment?" She also informed Oskar that she hoped "this Hindemith person" didn't compose too modernish music because she really liked Bach.

Apparently Oskar and Hilla still hoped that An American March would bring in enough. However, other interests already owned partial rights, and the amount finally designated for fees much exceeded the amount available from Oskar's grant. Ultimately, the music was not cleared for several years, during which time American March could not be screened for profit.

Along with An American March Oskar sent Rebay a print of the black-and-white version of the Paramount film, which she loved. By July 1941, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation offered Fischinger $1,300, nominally to help him buy the rights for the Paramount film, and prepare the first color prints. Once again, however, the terms of the grant demanded not only a print of the color version of the Paramount film but also a print of the next film Oskar produced; a laboratory cost nearly as large as the grant.

With the American March grant money Oskar had rented a studio upstairs from a Bank of America on Sunset Strip, and hired several women, including his wife, to fill in the colors on the cels. But when the American March money ran out, the Fischingers faced another six-month period of near starvation before the next grant money arrived. During that time, their rent at Normandy Village was so hopelessly behind that in August 1941, they had to move to a small house ($52 per month rent) at 1010 Hammond Street, just off the Sunset Strip. This turned out to be a very lucky move for them, since the landlord, Nelson McGrady, became a good friend. McGrady lived on a ranch in Camarillo, where he grew avocados and kept rabbits and chickens, which he shared with the Fischingers liberally, throughout the war years when ration stamps and food shortages would add to their chronic poverty. In the yard of the Hammond Street house stood mature orange and lemon trees that bore fruit year 'round, and the yard was large enough for a vegetable garden, so for the first time since 1936, the Fischingers enjoyed a degree of comfort and security.

In September 1941, Oskar's friend and lawyer, Milton Wichner, finally arranged for Oskar to buy the film from Paramount for $500 (they had wanted $1,500 originally, then $1,000 by February 1941). Ralph Rainger, the composer, kindly gave Oskar the music rights.

Through another stroke of luck, Orson Welles hired him in September to work at Mercury Productions for an RKO feature It's All True, which would have contained four short episodes, of which one, about the life of Louis Armstrong, would have included Oskar's abstract animations. Welles was supervising all four stories in simultaneous production, and before Oskar had a chance to do any substantial, specific work for the Armstrong project, the United States entered World War II in December 1941, and Welles was enjoined by Nelson Rockefeller and John Hay Whitney to change the focus of his feature to South America where Nazi and anti-U.S. influence was feared. Welles dutifully left for Rio to photograph the carnival, and Oskar presently received reels of samba soundtrack to experiment with. However, monetary and administrative changes in RKO and the CIA (detailed in Charles Higham's Films of Orson Welles, University of California Press, 1970), caused Mercury Productions to be ejected from the RKO lot in July 1942, and It's All True was cancelled. Oskar was given the Mercury Productions bulletin board as a souvenir, and since canvas was already scarce and expensive, he painted one of a series of nonobjective compositions on it.

The entry of the U.S. into World War II placed the Fischingers in new jeopardy. Oskar was now an "enemy alien." In 1937, the Fischingers had to drive to Mexico and reenter the country under a different immigration quota in order to stay in the U.S. and maintain a work permit (Oskar could not, at first, hold a regular job, but only be hired on contract for special productions). After they had children born in the U.S., their right to stay was assured, but the enemy alien status imposed severe strictures, including an 8:00 p.m. curfew, mail censorship, and ineligibility for employment in many jobs including anything to do with the film industry. They were also forbidden to have a short-wave radio in their home, and since their family radio contained a short-wave unit, they were forced to store it at their agent, Paul Kohner's office pending the end of the war. After some six months when it was clear the war would not be over soon, Oskar borrowed the radio back from Kohner to have the short-wave unit removed by a radio repair shop which must have reported Oskar to the F.B.I, since agents came to investigate the Fischinger's spying equipment. Fortunately, the shortwave unit was already back in Kohner's office. When the agents asked if the Fischingers had any "contraband," (an unusual English word they did not know), Oskar produced a small hatchet, at which point the F.B.I. men left, laughing.

Fortunately for Oskar, Orson Welles chose to keep him unofficially employed after December 1941, paying him privately, under the table. Since the script for Oskar's section of It's All True was never definitely established, he never did specific work for Welles, who graciously allowed him to use the studio facilities to prepare the color print of the former Paramount film, and to work on painting cels for other new films. After Mercury folded, Oskar was forced to ask Rebay for another $750 for the lab costs of drawing a color print of the "Paramount" film, meaning that the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation would have loaned $2,000 for the project. On September 26, 1942, Rebay wrote: "It was not easy for me to get even $1,000 agreed to, for we get very wonderful films from [Mary] Ellen Bute and McLaren for one-half or one-third your price... I think it outrageous that you speak of the starvation of your family when you spend money and time on painting for which you are not even gifted...something that only increases the amount of mediocrity in painting."

Allegretto, (c) Center for Visual Music

But by October 8, she had managed to get the $750 in exchange for a color print of the "Paramount" film, a second print of Composition in Blue, and a print of a new, intentionally silent film with a 78 frame rhythm (which might have been either the Organic Fragment, or Radio Dynamics. Rebay disliked the Paramount title "Radio Dynamics," and suggested the title "Allegretto" for the film (Bauer was fond of musical titles), which Fischinger immediately adopted, and a print of the new color version was delivered by February 1943. The Baroness von Rebay bitterly berated him for not having the intentionally silent film completed also, and in her April 26 letter observes: "I have found in dealing with Germans one is tricked more often than not," apparently forgetting that she was of German ancestry as well.

At this time, the specific object of Rebay's anxiety was really not Oskar but Rudolf Bauer. Apparently Bauer had fallen in love with and secretly married an American woman who lived at his home posing as a maid. When Rebay found out, she was heartbroken and furious. (After Hilla lamented to Oskar that she had gone to Bauer's house and discovered him lying naked on top of another woman, the irrepressible Oskar quipped, "Did she suppose he would do it in a tuxedo?") After some heated squabbles with Rebay, Bauer denounced her as a Nazi collaborator, resulting in her brief imprisonment as a horder and possible spy. While Solomon Guggenheim arranged for a speedy release from jail, the Baroness remained justifiably paranoid about the incident, since in addition to her monumental promotion of Bauer's work, she had also, with lavish funding from Solomon Guggenheim, rescued Bauer from a Nazi concentration camp, bought him an estate in New Jersey, two Dusenbergs, and established a monthly expense stipend for him. The pathetic tragic dimension of the Baroness emerges in the contradictions of her June 20, 1943 letter: ...Somehow Bauer is full of vanity and would like to run the Museum after his fashion and get the credit for everything I have done, but he cannot even speak English. I do not claim in the least to be an expert in anything; in fact, the more I learn the less I know, but I do know one thing that, most every day, I start work at 3:00 a.m. for this Foundation...You can well imagine how much I have to concentrate to get everything going and to plan it on time. It is a terrifying job considering that I cannot even discuss it with Bauer...

Oskar became unfortunately embroiled in the affair since Karl Nierendorf had asked Oskar to warn Hilla that Bauer had said he would betray her because he wanted to become director of the Foundation himself. Rebay even drafted several letters that she had Oskar retype and send to Bauer as his own, when she and Bauer had ceased speaking to each other.

As it became clear that friendly relations between the Baroness and Bauer were rather permanently severed, Rebay became more bitter, and Oskar became to some extent a scapegoat. In June 1943, Hilla agreed to give Oskar $200 each month for a year if he promised to finish three films: one synchronized to Bach's Brandenburg Concerto #3, one synchronized to John Cage's percussion music, and the intentionally silent film with a 78 frame rhythmic cycle. She required Oskar to give regular, detailed reports on his progress, and to acknowledge each of her letters by repeating key phrases.

In order that he improve himself spiritually, she also arranged for him, starting July 1943, to attend the Institute of Mental Physics in Los Angeles, a church run by a friend of hers, Edwin Dingle, who had adopted the Tibetan name "Ding Le Mei."

Looking over the correspondence between Oskar and Rebay during this period, it is hard to decide how to interpret things. Rebay obviously makes many exaggerations in order to humiliate Oskar in ways she would have liked to humiliate Bauer; and Oskar repeats things back to her with an exaggerated effusiveness that can only be satirical, for example, this exchange from October 1944:

Rebay: I had offered to loan my gorgeous canvas "Andante Cantabile" to the Institute of Mental Physics - but the offer was ignored - of course when it comes to taste one must be looking elsewhere as their book pamphlets, letterheads, and last color reproduction of flag and candlelight (did you see it) are very much indicating how they are backwards and unorganized in this respect - It is hard to believe - to my feeling the inner Chamber should have no purple...

Oskar: I am quite sure Dr. Dingle will be very happy to have your great picture "Andante Cantabile." I think your offer is really grand. This would bring for the first time one of your great paintings to California, so it can be seen by as many people as there are interested in it. And I think the Institute of M.P. is a good place to show it. When Dr. Dingle has given no reply to your generous offer, I think it is due to two facts: first, as a real Yoga, he shuns any involvement in other fields of expression, second; he does not know what it is all about...The flag and candlelight color reproduction hit me, too, in the stomach, but here maybe we have to be patient, too - The originators of Non-objective art are still alive and originators are mostly not much concerned with teaching. They teach through their work - and it needs a long time before the regular teachers grasp the Idea - Many generations are necessary to teach the masses...

These bi-monthly report letters had to be typed in good English, and Oskar spent days of anguished work on each one. When it came time to reporting how many cels he had completed for the Bach film, then, he felt justified in claiming about 500 each month, although he worked primarily on paintings each during that time: he had already, perhaps, devised the "motion painting" technique, but in any case, Rebay's comments about his painting were so particularly cruel that he had to pretend he was not painting.

To the extent that the Baroness has become something like a Wicked Witch of the East in this nightmare fairy-tale of Oskar's, Galka Scheyer becomes more and more like a Good Witch of the West. About the same age as Rebay and Bauer, Galka signed in 1924 as the official American agent for the paintings of Feininger, Klee, Kandinskyand Jawlensky, whom she named "The Blue Four." For twenty years she toured tirelessly, promoting their work and abstract art in general, giving lectures, classes in art for children, and arranging exhibitions. She lived not far from the Fischinger's Sunset Strip residence, and she made sure the family got by in hard times, hiring Oskar to maintain a "victory garden" in her yard, or hiring Elfriede to shop and cook for her, or whatever other pleasant and easy tasks she could devise. When she went away to New York, Oskar would act as caretaker for her dog Tuffy and her house, where Oskar could scrutinize and touch and meditate upon splendid Klees and Kandinskys. Unlike Rebay, Galka encouraged Oskar's own painting. At a time when Jawlensky, crippled with arthritis, painted simple canvases that Galka could not sell for $10, and Galka herself was buying a Picasso for $800 (in $30 per month payments), she arranged to sell one of Oskar's paintings (a fine mosaic, painted on glass, with the composition bursting out of its implied frame) to Katherine Dreier's Societe Anonyme for $250, but Oskar wanted $450 and refused to sell for less. Unfortunately, by 1944 Galka grew quite ill with cancer, and though she struggled painfully to be active until the last, she died in 1945, a sad personal loss for the Fischingers. Galka's superb collection of paintings is now in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

During the early '40s, Oskar threw his energy enthusiastically into painting. As an animator he had made many thousands of graphic compositions - about 1500 for each minute of each film - many more than the average painter ever does in a lifetime. He had developed extraordinary control of his drawing skill - he could execute straight lines freehand, and judge relationships with great precision - and he had an opportunity to study repeatedly, hundreds of variations on all kinds of compositions (and in the American cel animations, every element of color, shape and size could be substituted in fine gradations by shuffling the transparent cels). During this period, the Karl Nierendorf Gallery considered publishing a book consisting of Oskar's Study #8 rendered thoroughly in hundreds of photos, which Oskar prepared, choosing every few frames as they represented the best still compositions. All of this practical skill and experience brings a great richness and fine mastery to his canvases of the period, from the serene austerity of the 1942 Black and White Circle (with its dark zig-zags embossed by thick impasto in thin lines that channel the observer's glance across polar-opposite textures of grey/white parallel brush strokes) to the flamboyant vitality of the 1943 Snowflakes (with its brilliant colors matched by equally vivacious gestures of loose brush-stroking). He was in love with everything uniquely belonging to painting - each hue and effect, device and technique that could be used: He painted a tiny geometrical composition on milky glass, and painted a larger, sumptuous mosaic entirely with his fingertip. He used spatulas, sponges and etching tools to supply textures to rigid geometric forms (e.g., the 1941 Red Circle), or to create textures and divisions of color that are their own subject. Rebay feared Oskar's painting because it defied her preconceptions, but his painting is eclectic and eccentric because he worked alone and tried everything.Out of the $200 per month stipend, Oskar rented for $30 a storefront studio on Sawtelle Boulevard near the Veterans' Hospital and U.C.L.A. in Westwood. Artist's canvas was by then largely unavailable, but Oskar managed to get twenty pieces of celotex (a composition board) which he hung in a row around the walls of his studio. Instead of working exclusively on cels for Bach's Brandenburg Concerto #3 as he reported to Rebay, Oskar painted on all twenty celotexes simultaneously, strolling about the studio making a few lines here, a dash there, sponging an area, scraping a bit, etc. What an astonishing sight they must have been when they were all nearing completion! Oskar elaborated most of these paintings in many superimposed layers - a metaphorfor the hieratic or elapsed process - a style he increasingly favored, and brought to a brilliant fruition in the film Motion Painting #1 (1947), which presents the sort of dynamic temporal intermittence of imagery analogous to the new color science Oskar had written about in August 1940.

In addition to the paintings, Oskar did work on films. He began the Bach film several times in different media, ranging from traditional cel animations (he painted about 1000 of these, and shot about 500 on 35mm film), to black-and-white and colored pencil drawings on various sized papers, to technical experiments such as the moving "Yin-Yang" which he developed with layers of colored cellophane gels. At that time, the Baroness was quite enthusiastic about Charles Dockum's color organ. Not to be outdone, Oskar arranged his work table to look like a color organ, and sent the Baroness the following description along with photos on July 7, 1943:

...The first thing I made was to prepare the colors I used for this work in such a way that for each instrument the color used was especially balanced and mixed. For the three bass viols a special bass scale is mixed, and for the three cellos, the three violas and the three violins there are also special color scales. The colors are in little bottles which are placed like a color organ, 5 rows over each other and easy to reach. The color row scales are tuned as exactly as possible in the same mode as the instruments. The movements are free. The music I studied very carefully over and over again, reading the conductor's partiture, and I know by now every single note. I hope someday to have a cello in order to play it and get a better feeling for the bass section, which is the basis for the whole work...

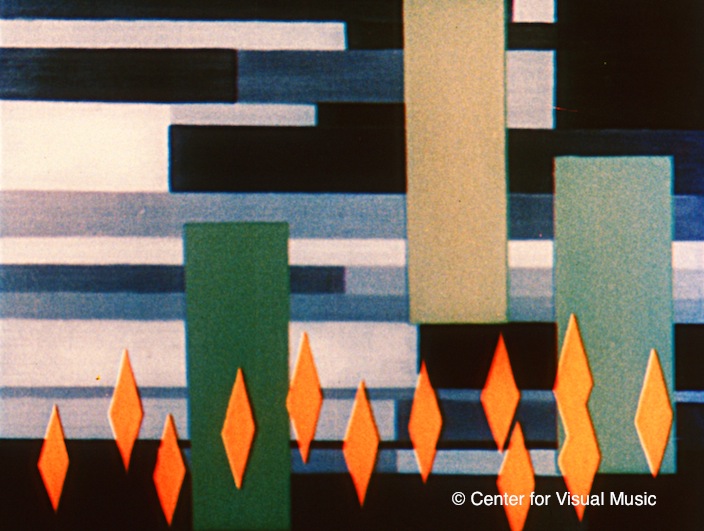

Images from Radio Dynamics

It must have been during this period that Oskar completed the film Radio Dynamics, as well. No overt reference is made to this film in the correspondence. Since Rebay did not like the old Paramount Rainger title which Oskar reused for this film, naturally he would not have mentioned it by that name to her. The "intentionally silent film with a 78 frame rhythm" mentioned several times during these years might be Radio Dynamics (of which about seventy-five percent falls into 78 frame phrases) or the sensuous Organic Fragment which remains unfinished and clearly has 78 frame "bars" numbered on the drawings. Perhaps the Organic Fragment, Radio Dynamics and other animation transparencies from this period (such as the superb silk-painting now in the Cinematheque Francaise which contains a perspective of small sub-screens containing the main image, like infinite reflections in parallel mirrors) were originally planned for the same silent film that was never finished, but a selection of completed footage was edited into Radio Dynamics.

The principle governing the design and final composition of Radio Dynamics is undoubtedly mystical, and during 1943-1944, Fischinger's Tibetan Buddhist leanings were being reinforced. Rebay required Oskar to attend Dingle's Institute (she said derisively) to improve his spiritual qualities. Rebay (and Bauer), who belonged to the first generation of nonobjective painters, still shuddered at the criticism that abstract art was just decoration - wall paper - and the sole defense against that charge (so brilliantly articulated by Kandinsky and Mondrian) seemed to them the spiritual values of the artist expressed in pure, "musical," Platonic, nonobjective rhythms. (Malevich's sociopolitical rapport with abstraction would not have amused the Baroness.) So Rebay cautiously painted according to certain "rules" of spirituality, prime among them being: "Avoid pattern and decoration at all cost!" Fischinger was just enough younger that nonobjective art seemed totally natural and obvious to him, and since he nurtured no mystique about the primacy of "oil on canvas" as an ultimate art medium, decorative pattern fascinated him as valid, spiritual folk-art form. Rather than suppress it, Oskar often used decoration consciously. He also broke almost every other "rule" of composition and color as laid down by Bauer ("Cosmic Movement," Der Sturm, Berlin 1918) and Kandinsky (Point and Line to Surface, Munich, 1926). Oskar's vast experience with kinetic arrangements and durational color mutation made him sensitive to a more adventurous range of possibilities. Oskar was not a follower; he was an original genius. The Baroness resented his unconventionality, and hoped to tame him into painting conservative, "party-line" nonobjective canvases by getting him involved with orthodox religious mysticism.

Since at least the late '20s in Berlin, Oskar had been fascinated by all forms of speculative scientific and mystical contemplations. Even though Oskar disliked formal organizations and never belonged to any social groups, he avidly studied all schools of mystic thought and enjoyed long Platonic dialogues with friends - most recently, at that time, with Galka Scheyer, who was particularly devoted to Krishnamurti. Quite aside from hating to attend two regular religious services each week (he had to take his daughter Barbara to Sunday School as well), Oskar found the atmosphere of Ding Le Mei's Institute of Mental Physics more akin to Protestant Puritanism than to the Tibetan Buddhism (with tantric Hindu roots) which it technically represented. Indeed, in 1944 the name was gradually changed to the International Church of the Holy Trinity and First Church of Mystic Christianity. However, he knew better at this point than to try to cross Rebay, although he shyly, slyly tried to suggest to her that he did have some spiritual roots, and perhaps did not need so much training (December 11, 1943):

...I'm very happy with the spiritual development through which I go now, and feel already a great improvement in my whole body, and I am very thankful for this. I wish I could write you how much this whole teaching is in line with my innermost tendency. Already in 1929, in Berlin, I invented or developed and used a rotating Cylinder, driven by a motor, day and night, all the time, to behold my Denials and Affirmations in steady motion-rotation. (Optical Poem reflects something of this.) Years later I learned about the Buddhist Prayer wheel, and discovered the existing parallel thoughts in my continuous rotating Cylinders and the thousands-of-years-old Prayer wheel. I was a little bit choked up to have made all on my own - as I thought - such a similar invention, and thought I was, at this time, the only one in Europe...

(The rotating cylinder is the source for Oskar's logo.) **

On February 25, 1944, Rebay wrote Oskar: "A religious non-objective film without music seems to me ought to be done. Did you ever run a film without music? Don't you think it is just as (if not even more) beautiful - a film without music, or if not without, simply with just sounds of knocking, flat or sharp, loud or soft, varied by the rhythmic interval of speed..." This is rather surprising, since Oskar's "Without Music / 78 fr. per bar" was included in a contract by October 1942, and a film to John Cage's percussion music (which contains plenty of "knocks") appears in the June 1943 contract. However, March 9, 1944, Oskar patiently answers:

...Your idea about the production of a religious non-objective film ought to be done, and could be done....You write in your letter that film does not need music necessarily, and can be even more beautiful without music. How true this is. The optical part, the form and the motion, is visualized through the visual imagination - through the phantasie of the Eye...Light is the same as sound: they are waves of different length that tell us something about the inner and outer structure of things. Non-objective expressions need no perspective. Sound is mostly an effect of the inner plastic structure of things, and also not needed for non-objective expressions...

Perhaps this interchange encouraged Oskar to edit Radio Dynamics. Several times he mentions that Dr. Dingle wanted him to show his films at the Institute, but he never says that he actually screened any there. And in several instances, Oskar was obviously using Ding Le Mei as a pretense for getting back a print of Optical Poem which Oskar had loaned to Rebay but which she now claimed was hers and would not return.

Another factor of this period which may have led to the perfection of Radio Dynamics was a new set of friends, the Bertoias. On June 25, 1943 Rebay wrote Oskar that she was having an exhibit of works she wished Oskar could see by a young Italian artist, Harry Bertoia. About a year later, Bertoia turned up in Hollywood, where he had moved with his wife Brigitta, daughter of Dr. William Valentiner, then curator of paintings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Bertoias lived on the beach near Topanga, where Harry (later famous for his kinetic-musical sculptures) was creating delicate woodcuts and monoprints on rice paper, and designing fine jewelry in silver. Oskar and Harry became instant comrades, and by the winter 1944, a great intimacy had grown between Oskar, Elfriede, Harry and Brigitta. Despite gas rationing, the Fischingers would pile into their 1932 Chevy with a rumble seat and drive to the beach whenever possible, and the Bertoias in turn drove to Hollywood as often as they could.

Harry and Brigitta were deeply spiritual, mystic people. Brigitta reveled in the mysteries of Astronomy and Astrology, and the secret rituals of tantric yoga. The couples went star-gazing and stayed up nights spinning out intricate philosophical discourse and experimenting with the possibilities of thought-transfer in meditative states. The warmth and joy and supportiveness of this new relationship may well have inspired Oskar's serenely energetic meditation film.

In November 1943, another daughter, Angelica, was born to the Fischingers, and the Baroness became her godmother, sending a hand-stitched, pink silk bonnet and gown for her goddaughter to wear for a christening at Ding Le Mei's Institute. Throughout the coming years, Rebay regularly sent many kind packages of clothes and other presents (ranging from war bonds to reproductions of Rebay paintings), to her godchild.

However, her relationship with Oskar remained as equivocal (one might say sadomasochistic) as ever. On one hand, she continued to invite him to submit paintings to each group show at her museum, and often as many as half-a-dozen were included in one exhibition. On the other hand, she scorned his paintings verbally, in statements ranging from hysterical, underlined shrieks "You cannot paint!" to confirmations of exacted promises: "I am glad that you will no longer waste your time and money on your not so significant paintings." The happy medium is perhaps best represented by her letter of October 11, 1943:

Many thanks for your little painting. I will try to show it in one of our shows, yet let me advise you that one chord is not a symphony or sonata yet, and I don't think painting is your most useful medium. Your ability is timed rhythm, it still seems to me. Your letter to Mr. Bauer was not good. He makes constant unbelievable trouble out of "Ehrsucht" (ambition) and vanity, and ignorance of earth conditions...I put a nice louse in my fur; my brother once warned me if I let him come over here.

A similar ambivalence is apparent in the events surrounding the plans for the new museum building. Rebay writes to Oskar asking advice, for example, about the safety precautions for preserving paintings and films, and when it is feared that robot-rocket-bombers might blitz New York, she asked were the art might be stored (Oskar recommended Denver!). In June, 1943, she announced to Oskar confidentially that Frank Lloyd Wright would be the architect for the new building (Ding Le Mei was using Wright as architect for a proposed City of Mental Physics near Twenty-nine Palms in the California Desert), and she solicited elaborate plans from Oskar for a film section (he designed complete production facilities and a dome theater). In May 1944, she paid for Oskar to come to New York to consult with Wright, and Oskar left New York so elated that on the three-day train trip back to Los Angeles, he drafted a joyous manifesto for The Non-Objective Kinetic Group which would be housed in the new museum and would include all the major practitioners of abstract film (among them Dwinell Grant, Len Lye, Mary Ellen Bute and Norman McLaren) sharing their skills and achievements. However, a few days after his return he received a chilling letter beginning: "I am glad you left when you did and wasted no further money on hotel rooms." After three paragraphs of bitter reproofs about Oskar's behavior in New York, and his relationship with Ding Le Mei ("...Please in the future stay away from Mr. Dingle...as he, out of kindness and very likely respect tor me, seems to give you far too much of his time...when you have really nothing of any importance to tell or say to such an important man."), the entire second page of the letter is devoted to a repeat of her objections to American March, concluding:

As long as you introduce the flag in a film, it should have been a flag film - nothing else. The flag should have appeared before the title, before the music begins. But this has never occurred to you very evidently, as in the American March there was no development of the lines, the stars, or the section themes of the flag themselves. I would first have made a fugue of the main theme, then introduced the stripes, then introduced the stars. Yet you probably do not understand at all what I am writing about and you would, as you should, never say: I do not understand. Too bad.

Greetings, sincerely yours, Hilla RebayApparently she didn't really mean any of this, because Oskar was still required to attend the Institute and Rebay continued to solicit plans for the new museum.

With the end of the war, conditions began to change, and Oskar was no longer so dependent on the Guggenheim Foundation. The Art in Cinema festivals at the San Francisco Museum of Art (and Cinema 16 in New York) mobilized the independent film community, and Oskar was at last recognized as a master in the U.S. The Museum of Modern Art took his films: Edward Steichen telegraphed Oskar January 16, 1952, "Abstract evening unqualified success. Your Motion Painting received tremendous ovation by packed auditorium. Would like to propose permanent acquisition set your films if feasible." Oskar's paintings were widely recognized, with one-man shows at the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Pasadena Museum.

How did Oskar really feel about Hilla Rebay? In response to her harsh letter after his New York visit in 1944, Oskar wrote her:

You, dear Baroness, are already far advanced and far ahead of us, in many ways, especially in the expression of artistic creative work. I could feel this very clearly when you were sitting in your screen-house. I still see you sitting there, and I cannot forget your Eyes and the beautiful light that came from you. In the train rolling away from New York, I saw you all the time, so like a wonderful, white Buddha, full of a fascinating life and light. When I was told to leave, I felt depressed and unhappy only because I could no longer see you...

To what degree was he being ironic or flattering? After 1947 when the Baroness, hating Motion Painting #1, refused to pay for the prints, and relations between Oskar and the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation were finally severed, Oskar expressed quite different feelings about her in an unmailed letter: "I always began to pray for you because I thought you went crazy. I hope you get well again and become your real self again... If I would be in your shoes, I would concentrate on being real humble - but humble throughout your heart, not only saying so."

But perhaps Oskar's true feelings about the Guggenheim Foundation and Hilla Rebay are best expressed by two delightful artworks he made around the end of the war. For Solomon's eighty-fifth birthday in 1946, Oskar bought him a turn-of-the-century mutoscope machine and painted a reel of 670 flipcards original animations in oil. Brightly colored concentric circles grow larger and smaller against a black background, and as they move in the black mechanical chamber of the mutoscope they seem to flutter a ghostly after-image. Oskar also made another reel with stars glittering like fireworks, comets undulating and sinuous lines copulating with each other, but he did not finish that reel and send it to Solomon. I think he liked Solomon very much anyway.

One of the most mischievous of Oskar's artworks is a series of seven collages he made by pasting cut-outs of Mickey and Minnie Mouse over reproductions of Bauer and Kandinsky paintings snipped from the Guggenheim catalogues. When Mrs. Fischinger and I first found these among the papers in Oskar's estate, we assumed they were meant as a satirical comment about Disney's fear of pure nonobjective imagery that had caused Oskar so much trouble during the making of Fantasia. But the style of the Mickey Mouse figures (cut from a newsprint publication like a comic book) bothered me a little. They looked more like the mature Mickeys of the Walt Disney Comics and Stories from around 1945, rather than the more child-like Mickeys of the prewar comics, the years Oskar might have been expected to make his satirical comments about Disney. Now I realize that the Guggenheim reproductions are just as much a part of this satirical juxtaposition. Was Hilla Rebay the Minnie Mouse of nonobjective art? Somehow, I guess Oskar must have appreciated the Baroness, too.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] For additional details of Fischinger's life and career, consult my article "The Films of Oskar Fischinger," Film Culture, no. 58-59-60, 1974, pp. 37-188. ***

[2] A full account of the Disney experience appears in Moritz's "Fischinger at Disney: or Oskar in the Mousetrap," Millimeter, February 1977, pp. 25-28.

[3] The original article was published missing the third footnote.

All letters quoted in this article and all photographs were part of the Estate of Oskar Fischinger, then the Elfriede Fischinger Trust, and are now copyright Center for Visual Music, since 2009. All rights reserved.

Additional CVM Notes:

* Later research has revealed that Composition in Blue did not win the grand prize at Venice, but a special prize .

** This assumption by Moritz was later called into question; Fischinger's daughter recalls the source of his logo as being a gyroscope.

*** Moritz expanded this Film Culture article, and corrected its errors, for his later biography of Fischinger: Optical Poetry, published in 2004.

The correct full titles of films mentioned in this article are An Optical Poem and An American March. An American March can be seen on CVM's Oskar FIschinger: Visual Music DVD release, 2017, along with Composition in Blue and other films.

Part II of this original article is about the Whitney brothers.

Images (c) Center for Visual Music, all rights reserved. Please contact us for permission to reproduce images, letters or quotes (cvmaccess at gmail.com)

NOTE: images were added by CVM; Moritz published black and white images from Allegretto which we have replaced with color images. Other images were not published with Moritz's original article, with the exception of the first one - b/w Oskar with Motion Painting panels.

Link to Oskar Fischinger: Ten Films DVD order page, which contains Motion Painting no. 1, Allegretto, Radio Dynamics and other films

Support the preservation and promotion of Visual Music - become a member of CVM! Vintage Fischinger premiums are available for Members (limited supplies).

Return to CVM Library

Go to CVM Home